Who Was Kaspar Hauser?

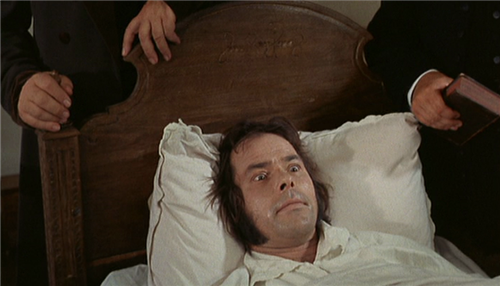

Kaspar Hauser was a foundling of about 16 years of age who appeared in Nuremberg in 1828. He was the object of considerable public curiosity and speculation and aroused the compassion of the city fathers. He claimed to have been confined in a dark cellar for years on end and to have been fed on a diet of bread and water. He arrived in the city barely able to speak and walked with great difficulty.

Here was a blank screen on which could be projected the fantasies of those with whom he came into close contact. Here was another of those wild children who people ancient mythology and who had appeared infrequently in Europe since the fourteenth century and had excited philosophers and medical men to speculate on the nature of man. How was a human being to be defined? How is speech acquired? Is man by nature good or evil? Are there any innate ideas? Do children have rights? Is civilization harmful or beneficial?

By 1828 some of these questions had lost their urgency, but faced with a youth who appeared to have grown up apart from human society there were many who wished to test their pedagogical and medical theories on such a promising subject. Much of the speculation about Kaspar Hauser was conditioned by the reaction of earlier intellectuals to previous cases of feral man. Nuremberg's intellectual elite was fully conversant with the writing of the likes of Montaigne, Rousseau and Voltaire and were eager to make their contribution to a debate to which so many distinguished writers had contributed. In our own day such cases are still of great interest, although the emphasis is now no longer on speculation about the nature of man but rather on the psychological effects of child abuse and the question of language acquisition. Few ask whether children have an innate conception of God, but the question still is raised whether children have an innate generative grammar. These questions are addressed in the first chapter which gives the intellectual setting to Kaspar Hauser's reception in Nuremberg on Whit Monday 1828.

The case of Kaspar Hauser was of particular interest to specialists in a number of different disciplines and thus provides us with fascinating insights into the climate of the times. This was the heyday of homoeopathy and Mesmerism, and 'animal magnetism' still had its devotees. Kaspar Hauser was put in the hands of a man who was fascinated by such forms of alternative medicine and he was placed in the care of homoeopathic doctors who conducted a series of experiments on their unfortunate patient. Kaspar Hauser appeared to be remarkably sensitive to homoeopathic medicines and was considered to have exceptional animal magnetism, particularly in his early days in Nuremberg. The doctors' reports thus provide interesting insights into these unorthodox but popular medical practices.

Kaspar Hauser claimed to have been kept in solitary confinement in a small, dark cellar for as long as he could remember. Under existing Bavarian law his gaolers were not necessarily liable for prosecution because it had to be shown that there were significant long-term harmful effects on the victim before a case could be made for abuse. Just as there had to be a corpse before anyone could be charged with murder so there had to be clear indication of abuse before charges could be laid. Kaspar Hauser appeared to be in good health, was not insane and insisted that he had been well treated, and thus no indictable crime had been committed. Under the Bavarian criminal code his gaolers could be charged with illegal confinement under articles 192 to 195 and with abandonment under article 174 but not for the lasting psychological damage they had inflicted on their victim. Anselm von Feuerbach, one of Germany's foremost jurists and the principal author of Bavaria's progressive criminal code, was fascinated by the case and took a kindly interest in Kaspar Hauser's welfare. In his remarkable pamphlet Kaspar Hauser: An Example of a Crime Against the Soul he argued that a dastardly crime had been committed against his soul, a crime that was far more serious in his view than either illegal confinement or abandonment. The debates between lawyers over child abuse and mental cruelty are indicative of current legal opinion on important issues that were only just beginning to be addressed.

When Kaspar Hauser arrived in Nuremberg he was barely able to talk and could only write the alphabet and his name. His education was first entrusted to a schoolmaster on sick leave who espoused progressive views on education that were tinged with the ideas of Jean-Jacques Rousseau. When it was felt that he was no longer safe in Nuremberg he was moved to near-by Ansbach where he was entrusted to a pedagogue with a radically different approach. He believed in strict discipline and learning by rote. These two opposing views on education illustrate how a change was taking place in Germany from the flexible and humanistic to the rigid and authoritarian.

Inevitably questions were soon asked about Kaspar Hauser's origins. He had become an overnight celebrity in Nuremberg. A steady stream of visitors came to his cell. Sensation seekers mixed with those who wished him well. Later, on his walks around the town he was surrounded by the curious. He was a local conversation piece, but soon his fame spread far and wide until he was christened 'Europe's Child'. But who was this strange youth? Whence did he come? Who were his cruel gaolers?

Most people were familiar with the fund of stories of foundlings, mysterious prisoners, and the intriguing drama of the 'Man in the Iron Mask'. Then as now there was a widespread belief in conspiracy theories. Combined with the popular radicalism of south-western Germany it was hardly surprising that it was widely believed that Kaspar Hauser was of noble or even royal birth. Why else should such pains have been taken to hide him for so many years? How else could it be explained that he was in remarkably good health and had clearly lived in hygienic surroundings? Was it not reasonable to presume that only the rich and powerful could have managed to cover their traces so successfully that the police, in spite of handsome rewards offered for any relevant information, were unable to uncover a single clue that might have helped them solve the mystery.

Radicals and republicans seized upon the Kaspar Hauser affair to discredit the petty principalities and what the great Prussian statesman Baron vom Stein described as the 'sultanates' of the German Confederation. Only such petty tyrants and their corrupt and ambitious satraps were capable of such cruelty. Only they had the dynastic or financial motives to remove an heir who stood in the way of a throne or a fortune. They alone had the power, the money and the organizational resources needed to cover all traces of their crime.

The proponents of this conspiracy theory were quick to seize on the grand duchy of Baden as the scene of the crime. Both male heirs had died in early infancy. The daughters were all perfectly healthy. Since the line of succession went through the male line, and since offspring of the Grand Duke's morganatic marriage to an ambitious schemer thus inherited the throne, there was a clear motive to remove the two legitimate male heirs. That Kaspar Hauser was the legitimate Grand Duke of Baden was explained by claiming that he had been exchanged when only a few days old with a baby that was mortally ill and who died a few hours later. He was then kept in captivity for about 16 years. He was now old enough to be able to pass as yet another of the homeless children that roamed the highways and byways of Germany. It was obvious that he had no notion of his exalted station and thus posed no danger to his kidnappers.

The suggestion that Kaspar Hauser might be the legitimate Grand Duke of Baden was of particular interest to the Bavarian authorities because of a complex claim to some previously Bavarian territory which should revert to them if the direct succession to the grand duchy of Baden were broken. Since Nuremberg was in Bavaria the police were bound to investigate the Kaspar Hauser affair, but the case was given an added importance because of the long-standing territorial wrangles with the neighbouring state. It is for this reason that the king of Bavaria took a particular interest in the case and offered a handsome reward for its solution.

It required a quite considerable leap of faith to believe that Kaspar Hauser was the first-born son of the grand duke of Baden and from the very beginning the theory was fiercely attacked by those who argued that he was simply an impostor who was leading a comfortable life at the expense of the taxpayers of Nuremberg. Many resented his fame, found his character unattractive, commented bitterly on his arrogance, his mendacity and his absurd pretensions to gentility. It was grotesque to people of a conservative bent that this somewhat ridiculous figure should be the darling of assorted radicals, devotees of alternative medicine and practitioners of experimental pedagogy. The 'anti-Hauserianers' saw the whole fuss as further evidence of the absurdity of radical pretensions and as an underhand attack on the established order.

Then as now investigative journalists had their political agendas, the sensationalist press concocted fabulous tales to increase circulation, and the public eagerly consumed the latest startling revelation. Kaspar Hauser became a media celebrity.

It was thus hardly surprising that Kaspar Hauser excited the interest of an eccentric British peer, Lord Stanhope, who had been educated in Germany, had a wide network of influential friends and acquaintances in Germany and whose Germanophile excesses caused no little comment at home. He first met Kaspar Hauser in Nuremberg in May 1831. He appeared to be entranced by the boy and believed that he must indeed be of high birth. He announced that he wanted to make him his ward, showered him with all manner of extravagant gifts and much to the relief of the authorities undertook to pay his expenses. Stanhope's abortive efforts to solve the mystery of Kaspar's birth left him angry and frustrated. He soon tired of Kaspar's affection, and what had appeared to him initially as innocent and charming he found tiresome and irritating. His passionate affection soon turned into a positive dislike and he changed sides to become a leader of the anti-Hauserianers. Stanhope's motives for becoming involved in the affair are mysterious. Various suggestions have been put forward. Was he merely intrigued by the case, seeing in Kaspar Hauser an entertaining curiosity and a mystery to solve? Was he acting as a political agent for some of the German courts and possibly for the British government? Did he hope to find further fame and fortune by restoring Kaspar Hauser to his rights? Was this merely a transitory homosexual infatuation?

Added to the mystery of Kaspar's past and the question of whether he had been the victim of a monstrous crime was the question of the attempt made on his life and his eventual murder. In October 1829 he received a severe gash on the forehead and claimed that he had been attacked by a mysterious man in black. Since no one had seen a stranger who matched this description some suggested that the wound had been self-inflicted. In December 1833 he died as the result of a knife wound which punctured his heart, liver and stomach. Once again the experts differed as to whether this was murder or a suicide.

The circumstances of Kaspar Hauser's death provided further material for both his supporters and his detractors. His supporters saw this as clear indication that he must indeed be the legitimate grand duke of Baden, for why should such an elaborate plot be hatched to dispatch a nonentity? His detractors argued that this was yet another attention- seeking device to win back Stanhope's affection.

From the ranks of the proponents of the crown prince theory came some staggering theories about the identity of his murderers. Strands of circumstantial evidence were woven together with imaginative abandon to show that the grand ducal house of Baden, the Zahringer, was deeply implicated in the murder. These suspicions were confirmed when most of the relevant papers in the possession of the family were destroyed and researchers were denied access to what remained.

The themes of a lost childhood, an imprisoned prince, a mysterious stranger, the outsider and the simple fool provided ample material for artists and a remarkable body of literature was inspired by the tale of Kaspar Hauser.

The protagonist in this remarkable story remains to this day a shadowy figure. He was a simple-minded youth who provoked both genuine affection and intense dislike. To some he appeared to be pure and innocent, to others mean-spirited, ludicrously vain and incapable of telling the truth. That he should excite such widely different emotions was due to the fact that he was the screen upon which so many different people projected their fantasies and beliefs. Here was living proof that man was inherently good - or the exact opposite. Kaspar Hauser showed that an innocent child was spoilt by a corrupting society, or was evidence that bad character was inherent and not learned. He was a crown prince robbed of his rights or a contemptible swindler. Was he the victim of a vicious crime, or did he inadvertently kill himself in an attempt to draw attention to his distress? Did he provide evidence for the power of homoeopathic remedies, or was he simply an epileptic given to convulsions? These and many other questions plagued contemporaries and the answers they provided give us many clues to the mentality of his times.

In a sense therefore Kaspar Hauser only really existed in the minds of those who projected their fantasies upon him. Of unknown origin, rumoured to be of noble birth, a simple soul who reflected mankind in a state of nature, here was a figure whom imaginative souls could easily mythologize. Much of the fascination of the Kaspar Hauser story was that it so easily fitted into a long tradition of foundling stories. He seemed to many to be in the line of succession to Moses, Joseph, Oedipus, Romulus and Remus, Gilgamesh, Siegfried and Parsifal. Some, such as Rudolf Steiner, were so carried away by such far-fetched analogies that they came to believe that Kaspar Hauser had some divine mission.

Freudians were later eager to quote the master's essay of 1909 'The Neurotic's Family Novel' to argue that the fascination of the case was due to the typical childhood fantasy that one is merely the adopted child of one's parents and that one's true parents are of exalted station. Adults suppress these fantasies which are then awakened when confronted with figures such as this mysterious foundling.

Contemporaries were fed with a rich diet of Gothic tales in which cellars and oubliettes, seemingly motiveless murders, anonymous letters, and vicious stepmothers played prominent roles. Germans eagerly consumed the novels of Ann Radcliffe and Horace Walpole and their German epigones, along with rich doses of trivial literature, and were thus well prepared to embroider the Kaspar Hauser story with all manner of exotic and horrific speculation.

Kaspar Hauser emerged from the obscurity of his mysterious past in the heyday of Metternichian reaction between the fall of Napoleon and the revolutions of 1848. The intellectual life of Germany was stifled by censorship, exile and emigration. The police rooted out revolutionaries and informants kept a close watch on subversives. The story of Kaspar Hauser, with the suggestion that he might be the heir to the grand duchy of Baden provided an ideal opportunity to attack the princes and to give vent to a widespread dissatisfaction with the existing order. Once the story became politicized it mattered little whether it was true or false. This was not lost on the authorities and their efforts to silence those who used the affair for political ends merely served to convince the opposition that they had a great deal to hide.

The ground was thus well prepared for Kaspar Hauser's arrival in Nuremberg. The story of a child held prisoner for years on end and who was possibly of noble birth fascinated those who had been nourished on myth and the Gothic romance. In the stifling atmosphere of the Germany of the Karlsbad decrees the opposition seized this opportunity to attack the established order and the repercussions were considerable. Others had a more limited agenda in welcoming the opportunity to study a wild child and test their theories whether medical or educational. His story also served to open an important debate on the appropriate legal response to child abuse.

That the story is of lasting interest can be seen in the stream of literary works that it has inspired. However enlightened we may feel ourselves to be today the mythical still has a strong hold upon us. We are still fascinated by violence, corruption and intrigue in high places. Addiction to conspiracy theories is as powerful as ever and the pushers, whether among the media or the politicians, are busy at work. Alternative medicine, experimental pedagogy and an obsession with the esoteric all have their place in the New Age. For those who are above all this there is the greatest attraction of the story of Kaspar Hauser. It is a rattling good yarn.

by Martin Kitchen

In: Kaspar Hauser: Europe’s Child (London and New York: 2001, pp. IX-XV)

The Caravan and the Desert

Tomaso Albinoni - Adagio G Minor / g-Moll

eu vi esse filme, triste muito triste, nao sabia q havia acontecido

ResponderExcluirIf you are looking for a good Cost Per Sale ad company, I recommend that you take a look at ClickBank.

ResponderExcluir