For nearly a decade now, we have been warned about an upcoming generation spawned from the electronic motherboard of interactive entertainment -- a youthful tribe of digitally-oriented citizens known as the Nintendo Generation. This is a stimulus-craving generation for which the video game replaces family interaction, supplants physical activity, and renders intolerable the unstimulating chore of reading held dear by the print-oriented literati for nearly five centuries. The Nintendo Generation is composed of misplaced, hyperactive digirati, highly specialized in the most advanced forms of entertainment and telecommunication, born on the cusp of rampant familial disintegration and overwhelming global unification. In an ongoing search for ecstasy, the young, fin-de-millennium digirati isolates himself from immediate social contacts, and channels his mental and physical energies into an ongoing war--a war waged against faceless opponents who are plugged into their individual outlets all along the fibre optic battlefield.

Yet the label of Nintendo Child is not limited to the video game enthusiast. Any child raised in the cable TV, music video, channel-flicking environment must be classified as part of the Nintendo Generation. In order to change channels, the pre-digital child had to get up from the sofa and turn the analog dial to any one of a sparse selection of local networks. The digital child, on the other hand, remains almost completely motionless before the screen, negotiating a dizzying landscape of visual images with the flick of a thumb or forefinger. In short, the remote-control-wielding channel-surfer is very much akin to the joystick-handling video game jockey--both seek solace before an interactive screen, enraptured by the flow of images which they (at least in part) control, while all the time vacillating endlessly between boredom and ecstasy.

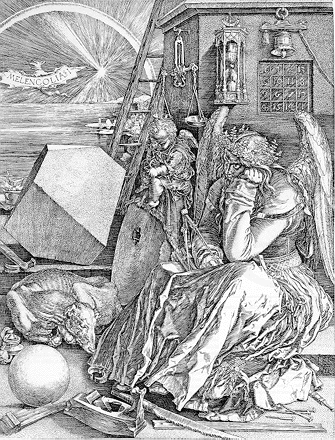

Notably, the Nintendo Child, rendered powerful before the video screen, has little chance of finding entertainment in the non-video world -- a world which is comparatively slow-moving, drab, and which may not be altered by the flicking of hand-held digital prostheses. Whereas the realm of video is explosive, brilliant, hyperstimulating, the real world lacks lustre--it is disillusioning, boring, unstimulating. We might even say that the prevailing mood of the Nintendo Child--aside from brief ejaculations of digital ecstasy--is melancholy. A melancholy comparable to the dark sobriety of the reformed drug-addict or alcoholic who forever abandons a heightened plane of experience. A melancholy that is reflected in the most prominant arts of the era: in fashion for which black is the only rule; and particularly in music, where such self-piteous and mundane lyrics as "I'm a creep," and "I'm a loser," are the anthems of an entire generation.

Ironically, just as the Nintendo generation seems to be reaching its cultural apex, Nintendo Inc. has ceased to be the grand facilitator of digital melancholia. The new God of video gaming is Sega, and the most powerful opiate for the digital masses is now the Sega Saturn system. In effect, the word Saturn encapsulates the very dichotomy that video game entertainment represents for the young digirati. In Ancient Greece, Saturn was identified with unrestrained merrymaking, orgy, ecstasy. Yet during the Renaissance, the word Saturnine began to be associated with sloth, melancholy and boredom -- Saturn was used as the alchemical term for lead. It is appropriate then, that Sega Saturn is a device which encourages and facilitates the Nintendo Child's endless vacillation between boredom and ecstasy, between sloth and hyperactivity, between melancholy and merry-making.

Saturn permits the digital youth to escape the boredom and melancholy of real life through a powerful dosage of hypers(t)imulated reality--a surreality then, which like a drug-induced psychosis, can only be described in terms of extraplanetary exploration. "Head for Saturn," the advertisers suggest. "Sega Saturn is like nothing else on earth." And yet, this promise of ecstasy is juxtaposed with a visual non-sequitur: the bust of a young, melancholic girl with a shaven head, wearing the rings of Saturn like a cyber-punk crown of thorns. Evidently, this youngster has a head for Saturn.

It is a head prone to fits of melancholy, unless it is immersed in the extra-terrestrial unreality (extra-terrestreality) of electronic games.

It would seem then, that the ultimate escape from this melancholic planet would not be to head for Saturn, or to possess a "head for Saturn," but to be gifted with an actual "head of Saturn"--a cybernetic head, half human, half electronic entertainment system. As the advertisements suggest,

to really understand what life is like on Saturn, look inside your head. There, in the inner realm of rods and cones, of optic nerves and ear drums, is where the Sega Saturn experience breathes. Three 32-bit orchestrated processors, 16.7 million colors, lightning-quick texture mapping, connoisseur-class surround sound, and amazing first-person perspectives immerse you in worlds of entertainment you've never experienced.

This is not just a "head for Saturn," but a "head of Saturn".

A utopic, cybernetic head conceived by the Sega God at the time of Genesis (Sega's original video entertainment system). By proclaiming to its consumers that "IT'S OUT THERE," the Sega God is not prophesying about a Promised Land on another planet. S/He is prophesying about a virtual extra-terrestreal oasis that only a cyber head would allow. S/He is promising a perpetual ecstasy which may be achieved without physically abandoning the Earth. Yet the Sega God's promise of ecstasy-through-video-narcotics is undermined by the war-camp aura of Sega's melancholy mascot.

There is nothing ecstatic about the Saturn Lady. Sega Saturn and other video game systems can only cause an escalation in the phenomenon of digital melancholy -- unless, of course, the Nintendo child is allowed to spend virtually all of his time immersed in the simulated world of video games--a solution which has been made accessible through such hand-held prosthetics as Game Boy and Game Gear. Unfortunately, these digital syringes of the Nintendo Child are beyond the scope of this study, and shall have to be examined at a later time.

*First Appeared in Dodo Magazine, July, 1995.

The technological imagination from the early Romanticism through the historical Avant-Gardes to the Classical Space Age and beyond

terça-feira, 23 de outubro de 2012

segunda-feira, 22 de outubro de 2012

Living Dolls by Caroline Evans

118 Cindy Sherman, Untitled 304, 1994, C-Print. Courtesy Cindy Sherman Metro- Pictures

In 1981 the German pop group Kraftwerk released a song, ‘Das Model’, in which they sang ‘she shows off her body for consumer goods’,highlighting the ambiguous status of the fashion model, whose own body becomes an object in the course of modelling clothes.(1) The film-makers The Brothers Quay made ‘Street of Crocodiles’ in 1986, based on the novella by Bruno Schultz, in which tailors’ dummies come alive and take over the tailor’s shop. They capture their former- master and dismantle him like a doll; treating him like a Stockman dummy, they measure him up, go through samples of fabric and trimmings and sew an outfit to dress him in. Comme des Garçons’ Metamorphosis collection for Autumn-Winter 1994-5 was photgraphed by the artist Cindy Sherman for the designers direct-mail campaign on slumped, dysfunctional dolls (fig.118). In the late 1990s, European designers like Martin Margiela, Hussein Chalayan and Alexander McQueen effected a similar reversal by substituting dummies for fashion models on the catwalk, or by playing on the robotic qualities of the model, stressing the inorganic at the expense of the organic.Their dummies or dolls echoed the ambiguous subject - object status of the model since the nineteenth century, recalling the opening pages of Zola’s novel about a nineteenth-century department store, The Ladies Paradise.The young country girl Denise arrives in Paris and is seduced by a shop window full of dummies, mirrored to infinity, dressed in the most sumptuous and elaborate fashions. The infinitely reflecting mirrors of the shop window seem to fill the street with ‘beautiful women for sale with huge price tags where their heads should have been’. (2) Zola’s image forces the commodity fetishism that figures prominently in his novel; and the ‘swelling bosoms’ and ‘beautiful women’ of the passage point to the complexity of the spectacle of femininity in Paris of the 1880s when women were both subjects and objects of consumer desire.(3)

Julie Wosk has argued that in the nineteenth century

artists’ images of automatons became central metaphors for the dreams and nightmares of societies undergoing rapid technological change. In a world where new labor-saving inventions were expanding human capabilities and where a growing number of people were employed in factory systems calling for rote actions and impersonal efficiency, nineteenth-century artists confronted one of the most profound issues raised by new technologies: the possibility that people’s identities and emotional lives would take on the properties of machines.(4)

And in the twentieth century, Hillel Schwartz has noted, this is the prevailing view of modernism: ‘modern life, with its essentially industrial momentum, has processed our worlds and our bodies into dissociated, fetishised, ultimately empty and machinable elements.’ (5) These elements resurface in contemporary fashion imagery which substitutes dolls for models or makes models look like androids (see fig. 9). For one of her collections Shelley Fox researched the Victorian dolls section of the Bethnal Green Museum of Childhood in London. For the show, the jeweller Naomi Filmer created porcelain chin plates and dipped the models’ hands in wax to make them more doll-like. Martin Margiela based a collection on scaled-up dolls’ clothes with huge machine knitting and giant poppers (fig. 119). In a fashion spread from 2000 called ‘Dolly Mixture’ models dressed and made up to look like Victorian dolls were juxtaposed against images of real Victorian dolls dressed in similar clothes (figs 120 and 121). The spread played with scale, reproducing the dolls in the same size as the human models. All were styled to look creepily dysfunctional, with bald foreheads, hair askew and jerky poses, disturbingly reminiscent of Hans Bellmer’s doll from the 1930s. In a short accompanying text, Gaby "Wood cited Freud’s essay on the uncanny to explain ‘the hovering uncertainty between animate and inanimate’ that makes dolls inherently uncanny:

But what does doll history, this little set of parables, threaten for women? Is ‘living doll’ still a compliment? Why are fashion models still called mannequins? What these wonderful, unsettling photographs seems to say is: if you want your women to look like dolls, this is what that reality would be like - a mad, decaying, decadence, full of about- to-snap jointed limbs, dangling paranormal dances and balding Jills-in-the-box, ready to spring into horrible, inhuman laughter.’ (6)

The doll of these fashion pictures is a ‘familiar’, the structural inversion of the humanist subject, an alienated other. (7) But it is not gender-neutral: as Wood’s implies, the female doll or cyborg in particular can also be linked to the search for the perfect body in Western culture, often played out in the idealised images of women in fashion, as well as in the ubiquitous Barbie doll. ‘The desire for the right image . . . alienates women from them-selves, turning them into automatons.’ (8) Sadie Plant has argued that the association of women, modernity and the machine dates at least from the early twentieth century when the first telephonists, operators and calculators were women, ‘as were the first computers and even the first computer programmers.’ (9) But her utopian vision of women as instruments and images of progress and a better future is shadowed by a darker image of women as commodities in the age of mass production.

This shadow goes back earlier, to the Paris of the Arcades, and the fear of the shadow is discernible in Benjamin’s writing. His jottings include this fragment: ‘No immortalizing so unsettling as that of the ephemera and the fashionable forms preserved for us in the waxworks museum’, a reference to André Breton’s Nadja in which the poet loses his heart to a wax mannequin of a woman adjusting her garter in the waxworks museum in Paris, the Musée Grevin. (10)

In 1993 at Viktor Kamp; Rolf’s first staged show the models climbed onto a pedestal and posed like classical sculptures. Annette Kuhn stated that ‘women are dehumanised by being represented as a kind of automaton, a living doll,’ (11) yet such images can be construed as a kind of ghosting of the alienating effects of modernity, specifically in relation to the female image. This point was implicit in the Imitation of Christ show in New York in which the more usual procession of live women on the catwalk was replaced by a fictional auction of clothes displayed on dummies. Benjamin’s notes include the phrase ‘Emphasis on the commodity character of the woman in the market of love.

119 Label for scaled-up doll’s clothes (enlarged by 5.2 times to human size). Martin Margiela, Autumn-Winter 1994-5. Photograph Anders Edstrom, courtesy La Maison Martin Margiela

The doll as wish symbol.’(12)

For Theodor Adorno, too, in his 1931 lecture on Dickens’s The Old Curiosity Shop, the waxworks museum, the puppet theatre and the graveyard were all equally ‘allegories of the bourgeois industrial world.’ (13) In Dickens’s Our Mutual Friend, Jenny Wren, the tiny dolls’ dressmaker, is contrasted with Mr Venus, taxidermist and articulator of human bones’ who assembles human skeletons for sale from miscellaneous body parts.(14) By inference, Jenny Wrens dolls are the equivalent of Venus’s skeletons constructed out of dead fragments and body parts. The figure of the anatomist’ who recycles human remains is the shadow of the ragpicker (a figure who also appears in the novel, and is one of its few benign characters, the Jew Riah). To emphasise the madness of this world of inversions, Jenny Wren refers to her father as her child, to Riah as her god-mother, to dolls as human and to humans as dolls. And in a final dark touch, as if to underline the capitalist base of the enterprise, and to remind us that this is a novel about money and its influence and, therefore, about the rot and the dead matter at the heart of capitalist life, human teeth continually drift into the change in Mr Venus’s till.(15)

120 Michael Baumgarten, Dolly Mixture, The Observer Magazine 2000. Styling Jo Adams.dress and underkirt by Yoi Yamamoto. Potografh courtesy Michaelm Baumgarten

In 1894 Scientific American showed an illustration of a French talking doll who sings and laughs ‘in a clear childish voice’ and recounts how her mother will take her to the theatre.(16) It also shows the American equivalent being manufactured in the factory of Thomas Edison, who invented the phonograph in 1877 and half of whose factory was given over to the manufacture of phonographic dolls (fig. 122). The central image shows us the young woman recording the doll’s utterance onto a wax cylinder. On either side we see the doll, dressed on the left and undressed on the right, to reveal the talking mechanism inside. The image below shows Edison’s factory, in which a great number of people are at work producing the dolls. The text accompanying this illustration perfectly describes the alienating effect of the modern production line:

121 Michael Baumgarten, Dolly Mixture. The Observer Magazine, 2000. Styling jo Adams, skirt by Chanel, underslip doll’s own. potogra courtesy Michael Baumgarten

Edison has no less than 500 people employed in manufacturing phonographs and half of them work in the doll department. Walking through the factory, one is filled with admiration for the order which prevails everywhere. Everything is done in the American way and the principle of the division of labour is most extensively applied . . . About 500 talking dolls ready to play can be supplied every day. In the centre of the picture a female employee can be seen speaking the words on to the wax cylinders one by one. (17)

Thus in the most up-to-date modern factory we witness the young woman robotically speaking each individual utterance, five hundred times a day, onto the wax cylinders in order to produce the living or, at least, talking simulacrum of the human female. The animated doll acquires some of the lifelike qualities of the living girl, while the girl trades semblances with the doll in her mechanical and repetitive utterances, to invoke Marx’s description of commodity fetishism whereby workers are increasingly dehumanised and consumers begin to live out their lives in and through commodities. (18) As people and things trade semblances the commodity assumes an uncanny vitality of its own (‘ “dead labour” come back to dominate the living’ (19) ) while the human producer acquires some of the ‘deathly facticity’ (20) of the machine. All is done in the name of progress, ‘the American way’, which was exemplified by Henry Ford’s production line in the early twentieth century. In figure 122 Marx’s concept of the worker’s alienation through the processes of industrial production is fused with the image of the woman as spectacle and commodity; and, in the age of mass production, the commodity is no longer unique but endlessly repeatable.

The image finds an echo in the Tiller Girls of, for example, the Weimar period in Berlin and the Rockettes of New York’s Radio City Music Hall in the 1930s, whose identical heights, synchronised dance routines and uniform costumes denied the material difference of sixty-four female bodies (fig. 123). Siegfried Kracauer in his article of 1927 ‘The Mass Ornament’, written while working as a journalist for the Frankfurter Zeitung, described the patterns made by chorus lines as ‘building blocks and nothing more . . . only as parts of a mass, not as individuals who believe themselves to be formed from within, do people become fractions of a figure.’ (21) Kracauer argued that the chorus line was a symbolic form of representation of ‘the capitalist production process’, singling out the Taylor system and the worker on the production line, for the massed forms of the cabaret entertainer are ways of visualising ‘significant components of reality’ that have become ‘invisible in our world’. ‘The mass ornament is the aesthetic reflex of the rationality to which the prevailing economic system aspires.’ (22) In other words the industrial aesthetic of modernity pictures its economic origins, and this is true no less of the fashion model than of the chorus girl. At the end of the twentieth century, as much as at the beginning, the uncanny replication and standardisation of the female form, in the shop window dummy, the showgirl or the fashion model, brings together two ideas: the idea of femininity commodified in an age of as cogs in a machine.

123 The Rockettes, Radio City Music Hall, New York, 1930s

The same visual shock tactic is often deployed at the end of the contemporary fashion show when all the models parade down the runway: fashion, supposedly about individuality, is actually about uniformity, and designers like Issey Miyake have fruitfully exploited this to dramatic ends (fig. 125). The body which is produced is a disciplined, streamlined and modernist body, in which the outer discipline of the corset has given way to the inner disciplines of diet and exercise. In the 1920s the designers Coco Chanel and Jean Patou designed for a body which conformed with the modernist aesthetic, which was functional and anti-decorative; this body was, and continues to be, ‘produced’, through diet and exercise, very much along the lines of Fordist production. (23) In the same way the uncanny cloning of Busby Berkeley’s musicals of the 1930s echoes Henry Ford’s production line in the early years of the century. Today one might find the same echo in Donna Karan’s uniforms’ for working women, the toned models of her shows or in Adel Rootstein’s dummies, which are modelled from the bodies of real individual models to produce generic types.

A photograph of 1990 shows the model Violetta in profile next to the Adel Rootstein dummy modelled on her (fig.124). They are posed in double profile, the one echoing the other, her hand resting on her Doppelganger’s shoulder. The two identical profiles are striking: which is the real woman, which the copy? The double portrait demands a double take. If the economic transactions of mercantile capitalism are uncanny, it is because they enable this slippage between animate and inanimate, life and death, subject and object. The image suggests the living model is merely an up-to-date variant of the inanimate dummy; the process of fetishism - in this case commodity fetishism - enables the displacement of meanings and motifs from the living woman onto the doll. Or does it? The theory of fetishism, be it commodity or sexual fetishism, is predicated on there being an original, organic, object of desire, from which feelings are displaced, but the entire relationship of model and mannequin and their historical origins call into question the nature of an original, especially when the two together appear almost indistinguishable. (24)

124 Model Violetta next to a mannequim by Adel Rootsein (relesead in 1990). Photography courtesy Adel Rootstein

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the fashion doll was the plaything of adult women, in the sense that dolls dressed in the latest fashions were sent from Paris to guide dressmakers towards fashion trends. Immediately after the Second World War the French Syndicat de la Couture Francaise created the Theatre de la Mode, a collection of dolls dressed by Parisian couturiers that was sent round the world to promote French couture. Thus even if clients did not initially go to Paris themselves the dolls wore the clothes instead, something that Viktor& Rolf may well have had in mind in their 1996 miniature show with dolls dressed in hand-made outfits (see fig. 59a). (25) Susan Stewart describes how, after the death of Catherine de’ Medici’s husband, eight fashion dolls were found in the inventory of her belongings, all dressed in elaborate mourning garb. Stewart also reminds us that ‘the world of objects is always a kind of “dead among us” ’ and that the toy is a reminder of this: ‘as part of the general inversions which that world presents, the inanimate comes to life.’ (26) Freud believed that children expect their dolls to come to life: ‘the idea of a “living doll” excites no fear at all.’ (27) His essay on the uncanny (unheimlich)

125 Issey Miyake, Spring-Summer 1999. Photograph courtesy Fashion Group International

opens with a discussion of E. T. A. Hoffmann’s ‘The Sandman’ which contains the original of the doll Olympia that appears in the first act of Offenbachs opera Tales of Hoffmann, the biddable and charming fiancee who turns out to be an automaton. Although Freud goes on to play down the significance of the doll, in order to bring forward the theme of castration, nevertheless he opens his discussion by referring to the uncannyness of waxworks, dolls and automata in their resemblance to living figures, and vice versa.(28)

The fashion dummy posed next to the real mannequin in the photograph is both a doll, uncannily posed against her human, and a double. Freud discusses the double too as uncanny in that it is simultaneously a reassurance against the threat of death and annihilation and a terrifying challenge to human individuality.(29) He recalls his own uncanny dream of a red-light zone (‘nothing but painted women’) to which he inexplicably doubles back at every turn. (30) Despite Freud’s disavowal of the themes of femininity and dolls, the unheimlich figure of the painted woman is the figure to which all roads return. And after canvassing several more examples he concludes his discussion with the suggestion that ‘to some neurotic men’ femininity itself might be uncanny: the female body, in particular its internal and external sexual parts, are both heimlich and unheimlich. (31)

In the shadow world of capitalist excess, the contemporary model is the uncanny double of the historical mannequin, in both her inanimate and her animate incarnations. The uncanny doubling that recreates the model in the dummy’s image also multiplies on the catwalk, endlessly replicated in the models’ generic beauty, ‘mirrored to infinity’ like the dummies in the shop window described by Zola in The Ladies’ Paradise. The uncanniness of the double is fused with the uncanniness of twins in Alexander’s McQueen’s redheaded twins in his snowstorm show (fig. 126). Thus the fashion model invokes the twin themes of doubling and deathliness. Mark Selzer has identified the late twentieth-century model with trauma and deathliness, linking the uncanny doubling and repetition of the model’s body on the catwalk (fig. 127) to the structure of trauma itself, with its acts of compulsive repetition. He describes

the stylized model body on display, a beauty so generic it might have a bar code on it; bodies in motion without emotion, at once entrancing and self-entranced, self-absorbed and vacant, or self-evacuated: the superstars of a chameleon-like celebrity in anonymity. (32)

Selzer comments on the way in which ‘the public dream spaces of the fashion world’ reduce the model to an object with deathly connotations, assimilating the animate to the inanimate, citing Benjamin that fashion ‘couples the living body to the inorganic world’, ‘it asserts the rights of the corpse’, and that ‘this is the sex appeal of the inorganic’. (33) In the period in which Selzer made this analysis the supermodels were being displaced by more waif-like figures such as Kate Moss. This imagery was given added potency by the publicity given to the lifestyle of many models in the 1990s, in which substance abuse and eating disorders were prevalent, and in which enormous pressures were put on already slender models to remain thin. And in July 2001 The Face featured a fashion spread by Sean Ellis that actually used a skeleton posed like a dressmaker’s dummy.

126 Alexander McQueen. The Overlook, Autumn-Winter 1999. Photograph Chris Moore, courtesy Alexander McQueen

127 Finale of a fashion show, 1990s. Photograph Niall McLerney

If the fashion model at the end of the twentieth century was deathly this was not based on superficial resemblance of lifestyle or body shape but, rather, on an underlying structural connection to her industrial origins, the connection I have traced to doubling and mass production in nineteenth-century consumer capitalism. Girls may come and girls may go; in the 1990s the fashion for waifs replaced the fashion for supermodels. (34) Yet, despite the deathly connotations of ‘grunge’ and ‘heroin chic’, as these visual styles were termed, in the 1990s the sheer perfection of the supermodel remained the more deathly version, because more generic, than the singularity and quirky imperfections of the models who followed in their place, such as Devon Aoki and Karen Elson. Recognising this, the cultural commentator Steve Beard looked back, at the close of the decade, in the British style magazine i-D:

Kristeva argues that the ultimate abject body is the human corpse. The human corpse aestheticised and galvanised then comes very near to conjuring the aura of the catwalk model. The supermodels of the last ten years have been compared to assembly-line cyborgs, sci-fi posthumans and wannabe transsexuals but perhaps the likes of [Cindy] Crawford and Claudia Schiffer were always closer to walking corpses than anyone dared to imagine. (35)

NOTES:

1. Caroline Evans, ‘Living Dolls: Mannequins, Models and Modernity’, in Julian Stair (ed.), The Body Politic, Crafts Council, London, 2000: 103.

2. Emile Zola, The Ladies’s Paradise, trans. with an intro, by Brian Nelson, Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York, 1995: 6.

3. Janet Wolff, ‘The Invisible flâneuse. Women and the Literature of Modernity’, Feminine Sentences: Essays on Women and Culture, Polity Press, Cambridge, 1990: 34-50; Mica Nava, ‘Modernity’s Disavowal: Women, the City and the Department Store’, in Pasi Falk and Colin Campbell (eds), The Shopping Experience, Sage, London, Thousand Oaks and New Delhi, 1997: 56—91. Christopher Breward, The Culture of Fashion, Manchester University Press, Manchester and New York, 1995: ch. 5, ‘Nineteenth Century: Fashion and Modernity’: 145-79.

4. Julie Wosk, Breaking Frame: Technology and the Visual Arts in the Nineteenth Century, Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, 1992: 81.

5. Hillel Schwartz, ‘Torque: The New Kinaesthetic of the Twentieth Century’, in Jonathan Crary and Sanford Kwinter (eds), Incorporations, Zone 6, Zone Books, New York, 1992: 104. Schwartz himself, however, disagrees with this interpretation of modern life.

6. Gaby Wood, ‘Dolly Mixture’, The Observer Magazine, 27 February 2000: 36-41.

7. Y Sobchack, ‘Postfuturism’, in G. Kirkup et al (eds), The Gendered Cyborg: A Reader, Routledge in association with the Open University, London, 2000: 137.

8. R. Fouser, ‘Mariko Mori: Avatar of a Feminine God’, Art Text, nos 60—2, 1998: 36.

9. Sadie Plant, ‘On the Matrix: Cyberfeminist Simulations’, in Kirkup et al. Gendered Cyborg: 267

10. Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, trans. Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin, Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., and London, 1999: 69.

11. Annette Kuhn, The Power of the Image: Essays on Representation and Sexuality, Routledge, New York and London, 1985: 14.

12.. Benjamin, Arcades Project. 895.

13. See Esther Leslies discussion of Adornos lecture in Walter Benjamin: Overpowering Conformism, Pluto Press, London and Sterling, Va., 2000: 10—11.

14. Charles Dickens, Our Mutual Friend, ed. with an intro, by Stephen Gill, Penguin, Harmondsworth, 1985 [1864—5]: 128.

15. Ibid: 125.

16. Reprinted in Der Natuur, 26 April 1894, trans. and reproduced in Leonard de Vries, Victorian Inventions, John Murray, London, 1971: 183.

17. Ibid.

18. Karl Marx, Capital, vol. 1, trans. Ben Fowkes, Penguin, Harmondsworth, 1976: 165.

19. Hal Foster, Compulsive Beauty, MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass., and London, 1993: 129.

20 Hal Foster, ‘The Art of Fetishism’, The Princeton Architectural Journal, vol. 4 ‘Fetish’, 1992: 7.

21 ‘The Mass Ornament’ [1927] in Siegfried Kracauer, The Mass Ornament: Weimar Essays, trans. Thomas Y. Levin, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., and London, 1995: 76.

22. Ibid: 76-9.

23. Peter Wollen, Raiding the Ice Box: Reflections on Twentieth Century Culture, Verso, London and New York, 1993: 20-1 and 35-71.

24. For a discussion of doubling, see Hillel Schwartz, The Culture of the Copy, Zone Books, New York, 1996.

25. Viktor & Rolf Haute Couture Book, texts by Amy Spindler and Didier Grumbach, Groninger Museum, Groningen, 2000: 8.

26. Susan Stewart, On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection, Duke University Press, Durham, N.C. and London, 1993: 57.

27. Sigmund Freud, ‘The Uncanny [1919] in Works: The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, under the general editorship of James Strachey, vol. XVII, Hogarth Press, London, 1955: 223.

28. Ibid: 226.

29 Ibid: 235—7.

30 Ibid: 237.

31. Ibid: 245.

32. Mark Seltzer, Serial Killers: Death and Life in Americas Wound Culture, Routledge, New York and London, 1998: 271.

33 Benjamin, Arcades Project, cited in ibid.

34. For a discussion of the relation among fashion, women and fluctuating body ideals, see Rebecca Arnold, ‘Flesh’, in Fashion, Desire and Anxiety: Image and Morality in the Twentieth Century, I. B. Tauris, London and New York, 2001: 89-95.

35. Steve Beard, ‘With Serious Intent1, i-D, no. 185, April 1999: 141.

In: Fashion at the Edge: Spectacle, Modernity, and Deathliness. Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2003, pp. 164.176.

domingo, 21 de outubro de 2012

In Memory of all Victims of Flight AF 447

Brothers In Arms

Those mist covered mountains

Are a home now for me

But my home is the lowlands And always will be

Some day you'll return to

Your valleys and your farms

And you'll no longer burn

To be brothers in arms

Through these fields of destruction

Baptism of fire I've witnessed your suffering

As the battles raged higher

And though they did hurt me so bad In the fear and alarm

You did not desert me

My brothers in arms

There's so many different worlds

So many different suns

And we have just one world

But we live in different ones

Now the sun's gone to hell

And the moon's riding high Let me bid you farewell

Every man has to die

But it's written in the starlight

And every line on your palm

We're fools to make war

On our brothers in arms

-Luiz Roberto Anastacio, 50; Brazilian; president for South America, Michelin

-Mateus Antunes, Brazilian

-Octavio Antunes, Brazilian

-Patricia Antunes, Brazilian

-Stephane Artiguenave, 35; French; salesman at electrical distributor CGED

-Sandrine Artiguenave, 34; French

-Silvio Barbato, Brazilian, former conductor for the Rio de Janeiro Municipal Theater Orchestra

-Valnizia Betzler, Brazilian

-Pierre-Cedric Bonin, 32; French; co-pilot of AF447

-Pedro Luis de Orleans e Braganca, 26; Brazilian; descendent of Brazil's last emperor

-Isabelle Bonin, 36; French; wife of AF447 co-pilot Pierre-Cedric Bonin

-Aisling Butler, 26; Irish, of Roscrea, Ireland; doctor

-Vanderleia Carraro, Brazilian

-Julia Chaves de Mirandas Chmi, Brazilian

-Leticia Chem, Brazilian

-Roberto Chem, Brazilian

-Vera Chem, Brazilian

-Chen Chiping, 53, Chinese; wife of Liaoning province's vice mayor, vice manager of a trade company under Benxi Iron & Steel

-Chen Qingwei, 35, Chinese; resident of central Chinese city of Wuhan, had applied to become Brazilian investment immigrant

-Brad Clemes, 49; Canadian from Guelph, Ontario; Coca-Cola executive

-Arthur Coakley, 61; British; structural engineer for PDMS

-Bianca Cotta, Brazilian

-Ana Luis Curty, Brazilian

-Leonardo Dardengo, Brazilian

-Juliana de Aquina, Brazilian

-Jose Roberto Gomes da Silva, Brazilian

-Carlos Eduardo de Mello, Brazilian

-Jane Deasy, 27; Irish; doctor

-Marc Dubois, 58; French; flight captain of AF447

-Simone Elias, Brazilian

-Marcia Mosconde Faria, Brazilian

-Sonia Ferreira, Brazilian

-Adriana Henriques, Brazilian

-Walter Carrilho Junior, Brazilian

-Izabela Kestler, Brazilian

-Jozsef Gallasz, 44; Hungarian; partner of Hungarian victim Rita Szarvas.

-Gao Jiachun, 27, Chinese; an employee with Huawei Technologies Co. Ltd. in south China city of Shenzhen

-Gao Xing, 39, Chinese; manager of trade company under Benxi Iron & Steel

-Antonio Gueiros; Brazilian; information systems director, Michelin

-Michael Harris, 60; American, from Lafayette, Louisiana; geologist

-Anne Harris; American, from Lafayette, Louisiana, physical therapist

-Erich Heine, 41; South African-born; member of executive board of ThyssenKrupp Steel AG

-Claus-Peter Hellhammer, 28; employee of ThyssenKrupp Steel AG based in Germany

-Veronica Ivanovitch, 57; Swiss-Brazilian; the wife of telecoms millionaire Hans Ivanovitch

-Moritz Kock, 54; German, from Potsdam; architect

-Giovanni Battista Lenzi, Trentino area, Italy

-Leonardo Pereira Leite, Brazilian

-Li Mingwen, 44, Chinese; deputy general manager of Benxi Iron & Steel based in China's northeastern Liaoning Province

-Jean Claude Lozouet, Brazilian

-Zoran Markovic, 45; Croatian, from Kostelji, Croatia; sailor

-Jose Gregorio Marques, Brazilian

-Maria Teresa Marques, Brazilian

-Nelson Marinho, Brazilian

-Carlos Mateus, Brazilian

-Gustavo Mattos, Brazilian

-Marco Antonio Camargos Mendonca, 44, Brazilian, worked for Vale SA mining company

-Luis Claudio Monlevad, Brazilian

-Tadeu Moraes, Brazilian

-Eduardo Moreno, Brazilian

-Marcelo Oliveira, Brazilian

-Christine Pieraerts; French; engineer at Michelin

-David Robert, 37; French; co-pilot of AF447

-Bruno Pelajo, Brazilian

-Marcela Pellizzon, Brazilian

-Ferdinand Porcard, Brazilian

-Sonia Maria Cordeiro Porcaro, Brazilian

-Deise Possamai, Brazilian

-Luciana Seba, Brazilian

-Shen Zuobing, about 40, Chinese; former material section chief, Benxi Iron & Steel

-Ana Carolina Silva, Brazilian

-Angela Cristina de Oliveira Silva, Brazilian

-Joao Marques Silva, Brazilian

-Jose Souza, Brazilian

-Adriana Sluijs, Brazilian

-Sun Lianyou, 49, Chinese; director of smelting plant, Benxi Iron & Steel

-Rita Szarvas; Hungarian; therapist at a Budapest center for children with motor disabilities. Her 7-year-old son was also aboard, but his name was not released.

-Maria Vale, Brazilian

-Francisco Vale, Brazilian

-Paulo Vale, Brazilian

-Eithne Walls, 29; Irish; doctor

-Solu Wellington Vieira de Sa, Brazilian

-Xiao Xiang, 35, Chinese; associate research fellow at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing

-Rino Zandonai; Trentino area, Italy.

-Christiane Zeuthen; Danish

-Zhang Qingbo, 54, Chinese; manufacturing department head, Benxi Iron & Steel

-Luigi Zortea; Trentino area, Italy.

My ticket in the same flight two weeks before the crash.

São Paulo- Rio de Janeiro - Paris - Hannover

17.05.2009

quarta-feira, 17 de outubro de 2012

Up in the Gallery by Franz Kafka Translation by Ian Johnston

If some frail tubercular lady circus rider were to be driven in circles around and around the arena for months and months without interruption in front of a tireless public on a swaying horse by a merciless whip-wielding master of ceremonies,

spinning on the horse, throwing kisses and swaying at the waist, and if this performance, amid the incessant roar of the orchestra and the ventilators, were to continue into the ever-expanding, gray future, accompanied by applause,

which died down and then swelled up again, from hands which were really steam hammers, perhaps then a young visitor to the gallery might rush down the long stair case through all the levels, burst into the ring, and cry “Stop!” through the fanfares of the constantly adjusting orchestra.

But since things are not like that—since a beautiful woman, in white and red, flies in through curtains which proud men in livery open in front of her, since the director,

devotedly seeking her eyes, breathes in her direction, behaving like an animal, and, as a precaution, lifts her up on the dapple-gray horse, as if she were his grand daughter, the one he loved more than anything else,

as she starts a dangerous journey, but he cannot decide to give the signal with his whip and finally, controlling himself, gives it a crack, runs right beside the horse with his mouth open, follows the rider’s leaps with a sharp gaze, hardly capable of comprehending her skill,

tries to warn her by calling out in English, furiously castigating the grooms holding hoops, telling them to pay the most scrupulous attention, and begs the orchestra, with upraised arms, to be quiet before the great jump, finally lifts the small woman down from the trembling horse, kisses her on both cheeks, considers no public tribute adequate, while she herself, leaning on him, high on the tips of her toes, with dust swirling around her, arms outstretched and head thrown back, wants to share her luck with the entire circus—since this is how things are, the visitor to the gallery puts his face on the railing and, sinking into the final march as if into a difficult dream, weeps, without realizing it.

spinning on the horse, throwing kisses and swaying at the waist, and if this performance, amid the incessant roar of the orchestra and the ventilators, were to continue into the ever-expanding, gray future, accompanied by applause,

which died down and then swelled up again, from hands which were really steam hammers, perhaps then a young visitor to the gallery might rush down the long stair case through all the levels, burst into the ring, and cry “Stop!” through the fanfares of the constantly adjusting orchestra.

But since things are not like that—since a beautiful woman, in white and red, flies in through curtains which proud men in livery open in front of her, since the director,

devotedly seeking her eyes, breathes in her direction, behaving like an animal, and, as a precaution, lifts her up on the dapple-gray horse, as if she were his grand daughter, the one he loved more than anything else,

as she starts a dangerous journey, but he cannot decide to give the signal with his whip and finally, controlling himself, gives it a crack, runs right beside the horse with his mouth open, follows the rider’s leaps with a sharp gaze, hardly capable of comprehending her skill,

tries to warn her by calling out in English, furiously castigating the grooms holding hoops, telling them to pay the most scrupulous attention, and begs the orchestra, with upraised arms, to be quiet before the great jump, finally lifts the small woman down from the trembling horse, kisses her on both cheeks, considers no public tribute adequate, while she herself, leaning on him, high on the tips of her toes, with dust swirling around her, arms outstretched and head thrown back, wants to share her luck with the entire circus—since this is how things are, the visitor to the gallery puts his face on the railing and, sinking into the final march as if into a difficult dream, weeps, without realizing it.

terça-feira, 16 de outubro de 2012

"Pi", Darren Aronofsky`s Masterwork: The Truth Made Flesh

Pi is an independent mathematical sci-fi thriller that pushes the envelope of the most controversial ideas of life itself, broad religion versus mathematics and order. In this film a brilliant number theorist, Maximilian Cohen, teeters on the brink of insanity as he searches for an underlying meaning of an elusive numerical code that is said to bare the secrets of the universe. Max lives in Chinatown, New York in a dark, claustrophobic apartment that is wall to wall consumed by his homemade super computer cleverly named Euclid. Cohen, a factual character, who to this day is continuously itching at the wonders of the meaning of pi, is played by Sean Gullette. In the film Max quotes his assumptions: "Mathematics is the language of nature. Everything around us can be represented and understood through numbers. If you graph these numbers, patterns emerge.

Therefore, there are patterns everywhere in nature." This philosophy is as delicate as any. Some believe in fait and chance, while others, like myself, construe a hypothesis that there is logical reason hidden behind everything in life, and that somewhere down the road there is eventually a simple cause and effect to any hurdle our universe can toss in front of us. The well known Chaos Theory, which supports ideas such as: Monsoons in Hawaii can inadvertently be caused by a slight pressure change from a migrating butterfly flapping its wings in Japan, is the standard that Cohen chooses to base his solitary, paranoia consumed life as he searches for a pattern in the most complex chaotic system known to man, the stock market. Max uses this man made "organism" as his data set.

As he grows closer to an omega truth, he is haunted by sociological handicaps, the very problems that every human suffers day to day. In one corner, an attractive neighbor symbolizes everything warm and caring, attempting to advert Cohen from his rigorous practices and bring him back down to earth. In another, he is the cat killed by curiosity, being plagued by vigorous migraine attacks caused by looking into the sun as a child. In yet another corner, he is harassed by two cliques representing everything materialistic: stockbrokers attempting to conquer the monetary market and Jewish mystics who believe a 216 digit number stumbled upon by Maximilian is the true name of God, leading to ultimate divinity. Throughout Max's attempted journey of anonymity, the director, Darren Aronoksy, uses many subtleties to capture Cohen's world of genius, anxiety and torment. This use of symbolism is commonly used in the movie and plays an important role in the portrayal of Pi. Euclid, his computer, along with Sol, his mentor and only trustee, in a way symbolizes Max's inevitable future. As they both grew closer to answer the unknown, they began breaking down, both catching a bug and eventually terminating themselves amidst great discovery. The closer Cohen grows to conquer his goal of affiliating a logical equation with the spiral and everything around us, the more it wears on him. He eventually realizes this and ironically "removes" his genius with the very drill he used to construct Euclid, to live a more surreal life.

In a demented way this represents how we are our own enemy, and have to defeat a part of ourselves to overcome obstacles. Another key artistic aspect for creating the world of p is its use of sound effects and music. Pi opts to depend solely on the use of futuristic electronica sound environments, composed by Clint Mansell. This is territory that has only been crossed by one other film, A Clockwork Orange, also musically inspired by Mansell. The correlation of the music in relevance to a particular scene is vital for setting the mood. All the scores are original pieces envisioned by the director and later perfected by the sought after musical artist. For instance, while Cohen is on the edge of discovery, the tempo grows faster and the tones more precise. This puts the audience on the edge of their seat as if they were on the verge of a breakthrough of their very own. While Max is in a state of flux or query, however, the music itself appears to ask a question with each flowing note.

If Maximilian is being interrupted by a pesky computer bug, the score trickles along like a minute ant and then throbs in an uproar of frustration and rage. Aronofsky also innovates a particular music theme aptly named "hip-hop" to coincide with reoccurring montages, such as moments of enlightenment, episodes of mass drug consumption and headaches. In hip-hop Aronofsky uses a flowing sequence of sounds and multiple short-framed pictures that, when pieced together, reflect a rhythm that transports the viewer into the realm of repetitiveness that Cohen must square up to day after day.

This can be calm and slow as he is thinking and watching is computer or quick and direct as the sound effects and screen shots of him popping pills and injecting morphine franticly pushing him forward in attempt to ease the pain. As depicted in Max's psyche, repetitiveness can be a powerful medium. This is another skill of directing endorsed by Darren Aronofsky. For example, many migraine sufferers are alerted of their upcoming headaches by numerous symptoms. In Cohen's case, it is a severe twitching of his thumb.

Once he starts jittering you cannot help but quiver for the upcoming thumping bass lines overlain with shrills reminiscent of a banshee that digs the viewer deep into Max's headache consumed cerebrum.

Immediately following the actual pain, Max enters a brief moment of hallucination, preceded by a nosebleed, and then a black out followed by a state of euphoria caused by heightened levels of dopamine. This sequence is repeated time and time again.

The concentration of this repetitiveness is so powerful it almost strikes as a warning, teaching one to ignore the temptations of curiosity. An act young Max succumbed to once he looked into the sun.

The director also takes advantage of the style of film itself. Pi is entirely featured in an extremely high-contrast black and white picture, at many times with little or no middle gray colors relevant.

Although it is entirely black and white, the clarity and sharpness of the picture dives down to the lowest and highest definition flawlessly capturing the status quo of Max's sanity. During Cohen's times of confusion and hysteria, the director chooses to inconspicuously capture the mood by shooting with a grainy chaotic picture.

Yet while Max is in control, or enlightened, the picture is extremely smooth and clear cut. Also, Aronofsky administered a new technique of filming perfectly apprehending Max's separation from the world around him. He devised a harness to attach a camera directly to the actor while he is running, called the snozzi-cam.

This feature mobilizes the actor while the environment around him twirls frantically, further putting the viewer into the characters point of view. Using such drastic, influential artistic measures often eludes the fact that all the ideas in p are factual, but the glue that holds the film together, the syntax between the lines, all came from "plagiarized" facts from textbooks and bibles.

In the end, after Maximilian Cohen is reconciled and returns to his place of enlightenment, I envisioned the closing scene being filmed in true color picture to induce one of the most powerful finales in film history, when it did not, I was briefly disappointed. Later to be engulfed with content realizing that nothing is perfect. To succeed, to overachieve, sometimes we must sacrifice other aspects, such as rogue scientist, Maximilian Cohen, in Pi.

segunda-feira, 15 de outubro de 2012

Robert Hughes`s Review on Stanley Kubrick`s "A Clockwork Orange" - The Decor of Tomorrow’s Hell "Time", December 27, 1971

Some movies are so inventive and powerful that they can be viewed again and again and each time yield up fresh illuminations. Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange is such a movie. Based on Anthony Burgess's 1963 novel of the same title, it is a merciless, demoniac satire of a near future terrorized by pathological teen-age toughs. When it opened last week, Time Movie Critic Jay Cocks hailed it as "chillingly and often hilariously believable." Below, Time's art critic takes a further look at some of its aesthetic implications.

Stanley Kubrick's biting and dandyish vision of subtopia is not simply a social satire but a brilliant, cultural one. No movie in the last decade (perhaps in the history of film) has made such exquisitely chilling predictions about the future role of cultural artifacts - paintings, buildings, sculpture, music - in society, or extrapolated them from so undeceived a view of our present culture.

The time is somewhere in the next ten years; the police still wear Queen Elizabeth Il's monogram on their caps and the politicians seem to be dressed by Blades and Mr. Fish. The settings have the glittery, spaced-out look of a Milanese design fair - all stamped Mylar and womb-form chairs, thick glass tables, brushed aluminum and chrome, sterile perspectives of unshuttered concrete and white molded plastic. The designed artifact is to Orange what technological gadgetry was to Kubrick's 2001: a character in the drama, a mute and unblinking witness.

This alienating decor is full of works of art. Fiber-glass nudes, crouched like Playboy femlins in the Korova milk bar, serve as tables or dispense mescaline-laced milk from their nipples. They are, in fact, close parodies of the fetishistic furniture-sculpture of Allen Jones. The living room of the Cat Lady, whom Protagonist Alex (Malcolm McDowell) murders with an immense Arp-like sculpture of a phallus, is decked with the kind of garish, routinely erotic paintings that have infested Pop-art consciousness in recent years.

The impression, a very deliberate one, is of culture objects cut loose from any power to communicate, or even to be noticed. There is no reality to which they connect. Their owners possess them as so much paraphernalia, like the derby hats, codpieces and bleeding-eye emblems that Alex and his mates wear so defiantly on their bullyboy costumes. When Alex swats at the Cat Lady's sculptured schlong, she screams: “Leave that alone, don't touch it! It's a very important work of art!" This pathetic burst of connoisseur's jargon echoes in a vast cultural emptiness. In worlds like this, no work of art can be important.

The geography of Kubrick's bleak landscape becomes explicit in his use of music. Whenever the woodwinds and brass turn up on the sound track, one may be fairly sure that something atrocious will appear on the screen - and be distanced by the irony of juxtaposition. Thus to the strains of Rossini's Thieving Magpie, a girl is gang-raped in a deserted casino. In a sequence of exquisite comedie noire, Alex cripples a writer and rapes his wife while tripping through a Gene Kelly number: “Singin' in the rain" (bash), “Just singin' in the rain" (kick).

What might seem gratuitous is very pointed indeed. At issue is the popular 19th century idea, still held today, that Art is Good for You, that the purpose of the fine arts is to provide moral uplift. Kubrick's message, amplified from Burgess's novel, is the opposite: art has no ethical purpose. There is no religion of beauty. Art serves, instead, to promote ecstatic consciousness. The kind of ecstasy depends on the person who is having it. Without the slightest contradiction, Nazis could weep over Wagner before stoking the crematoriums. Alex grooves on the music of “Ludwig van," especially the Ninth Symphony, which fills him with fantasies of sex and slaughter.

When he is drug-cured of belligerence, strapped into a straitjacket with eyes clamped open to watch films of violence, the conditioning also works on his love of music. Beethoven makes him suicidal. Then, when the government returns him to his state of innocent viciousness, the love of Ludwig comes back: "I was really cured at last," he says over the last fantasy shot in which he is swiving a blonde amidst clapping Establishment figures in Ascot costume, while the mighty setting of Schiller's Ode to Joy peals on the soundtrack.

Kubrick delivers these insights with something of Alex's pure, consistent aggression. His visual style is swift and cold - appropriately, even necessarily so. Moreover, his direction has the rarest of qualities, bravura morality - ironic, precise and ferocious. "It's funny," muses Alex, "how the colors of the real world only seem really real when you viddy them on the screen." It is a good epigraph to A Clockwork Orange. No futures are inevitable, but little Alex, glaring through the false eyelashes that he affects while on his bashing rampages, rises from the joint imaginations of Kubrick and Burgess like a portent: he is the future Candide, not of innocence, but of excessive and frightful experience.

In: Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange. Edited by Stuart Y. Mcdougal. Cambridge University Press, London, 2003, pp. 131-33.

Stanley Kubrick's biting and dandyish vision of subtopia is not simply a social satire but a brilliant, cultural one. No movie in the last decade (perhaps in the history of film) has made such exquisitely chilling predictions about the future role of cultural artifacts - paintings, buildings, sculpture, music - in society, or extrapolated them from so undeceived a view of our present culture.

The time is somewhere in the next ten years; the police still wear Queen Elizabeth Il's monogram on their caps and the politicians seem to be dressed by Blades and Mr. Fish. The settings have the glittery, spaced-out look of a Milanese design fair - all stamped Mylar and womb-form chairs, thick glass tables, brushed aluminum and chrome, sterile perspectives of unshuttered concrete and white molded plastic. The designed artifact is to Orange what technological gadgetry was to Kubrick's 2001: a character in the drama, a mute and unblinking witness.

This alienating decor is full of works of art. Fiber-glass nudes, crouched like Playboy femlins in the Korova milk bar, serve as tables or dispense mescaline-laced milk from their nipples. They are, in fact, close parodies of the fetishistic furniture-sculpture of Allen Jones. The living room of the Cat Lady, whom Protagonist Alex (Malcolm McDowell) murders with an immense Arp-like sculpture of a phallus, is decked with the kind of garish, routinely erotic paintings that have infested Pop-art consciousness in recent years.

The impression, a very deliberate one, is of culture objects cut loose from any power to communicate, or even to be noticed. There is no reality to which they connect. Their owners possess them as so much paraphernalia, like the derby hats, codpieces and bleeding-eye emblems that Alex and his mates wear so defiantly on their bullyboy costumes. When Alex swats at the Cat Lady's sculptured schlong, she screams: “Leave that alone, don't touch it! It's a very important work of art!" This pathetic burst of connoisseur's jargon echoes in a vast cultural emptiness. In worlds like this, no work of art can be important.

The geography of Kubrick's bleak landscape becomes explicit in his use of music. Whenever the woodwinds and brass turn up on the sound track, one may be fairly sure that something atrocious will appear on the screen - and be distanced by the irony of juxtaposition. Thus to the strains of Rossini's Thieving Magpie, a girl is gang-raped in a deserted casino. In a sequence of exquisite comedie noire, Alex cripples a writer and rapes his wife while tripping through a Gene Kelly number: “Singin' in the rain" (bash), “Just singin' in the rain" (kick).

What might seem gratuitous is very pointed indeed. At issue is the popular 19th century idea, still held today, that Art is Good for You, that the purpose of the fine arts is to provide moral uplift. Kubrick's message, amplified from Burgess's novel, is the opposite: art has no ethical purpose. There is no religion of beauty. Art serves, instead, to promote ecstatic consciousness. The kind of ecstasy depends on the person who is having it. Without the slightest contradiction, Nazis could weep over Wagner before stoking the crematoriums. Alex grooves on the music of “Ludwig van," especially the Ninth Symphony, which fills him with fantasies of sex and slaughter.

When he is drug-cured of belligerence, strapped into a straitjacket with eyes clamped open to watch films of violence, the conditioning also works on his love of music. Beethoven makes him suicidal. Then, when the government returns him to his state of innocent viciousness, the love of Ludwig comes back: "I was really cured at last," he says over the last fantasy shot in which he is swiving a blonde amidst clapping Establishment figures in Ascot costume, while the mighty setting of Schiller's Ode to Joy peals on the soundtrack.

Kubrick delivers these insights with something of Alex's pure, consistent aggression. His visual style is swift and cold - appropriately, even necessarily so. Moreover, his direction has the rarest of qualities, bravura morality - ironic, precise and ferocious. "It's funny," muses Alex, "how the colors of the real world only seem really real when you viddy them on the screen." It is a good epigraph to A Clockwork Orange. No futures are inevitable, but little Alex, glaring through the false eyelashes that he affects while on his bashing rampages, rises from the joint imaginations of Kubrick and Burgess like a portent: he is the future Candide, not of innocence, but of excessive and frightful experience.

In: Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange. Edited by Stuart Y. Mcdougal. Cambridge University Press, London, 2003, pp. 131-33.

Assinar:

Postagens (Atom)