In the

modern world, a certain level of scientific literacy is important for

understanding the latest discoveries in climate change, genetics, information

technology, and other fields that have a direct bearing upon the lives of

millions of people. However, there are many people within the United States who

are effectively unable to grasp the concepts involved in scientific discovery.

According to study published in the MIT

Technology Review, only 28 percent of Americans are

“scientifically literate.”

The

ability to understand scientific concepts is important for the overall vitality

and well-being of a civilization. The Islamic world was an early leader in

science during the Golden Age of Arabic beginning around the year 800. After several hundred years

of producing wondrous scientific achievements, such as charting the stars and

inventing mechanical water clocks, a growing climate of religious intolerance

towards the scientific enterprise doomed much of the Muslim world to becoming a

technological backwater. Similarly, the fall of Rome caused many discoveries to

be lost for nearly a thousand years and precipitated what is known today as the

“Dark Ages” in Europe: a time of superstition and low standards of living.

Likely

due, in part, to prevent a similar fate from befalling us, several public

figures have come forth. These individuals attempt to make the often-dry and

technical aspects of science accessible to the general public. Modern

techniques used for communicating science to the masses include television programs,

interviews, podcasts and popular social media channels.

Carl

Sagan, perhaps the most charismatic astrophysicist who ever lived, was one of

the early leaders in this type of science communication. Sagan was not only an

effective communicator but also a top-rate scientist with more than 600

published scientific papers to his name. In 1980, his Cosmos television

series was broadcast and captured the imagination of millions who were

entranced by the broad and beautiful vistas of the natural universe as portrayed

by Sagan. He wrote many scientific books for lay audiences, including Pale Blue Dot and the novel Contact, which was later turned into a

major motion picture.

It can

be said that the most notable present-day counterpart to Sagan is Neil deGrasse

Tyson, astronomer and cosmologist. He is the director of the Hayden Planetarium in New York City and also

works for the American Museum of Natural History. For anyone who saw last

year’s reboot of the Cosmos

program, it’s clear that Sagan’s influence on the starry-eyed Tyson

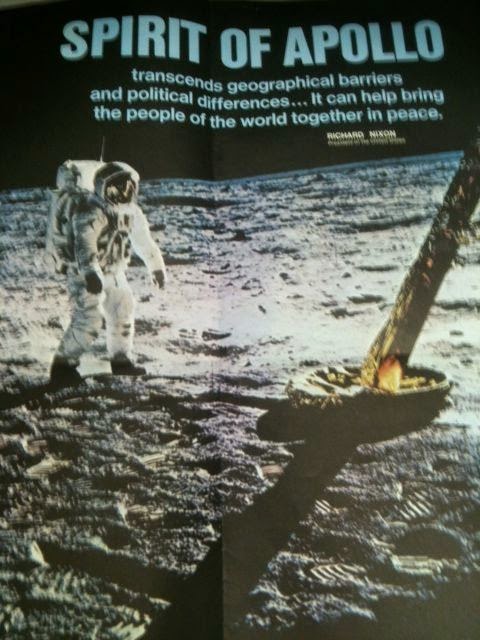

went far beyond their one-time meeting on Cornell’s campus. Sagan’s personal beliefs in

the cultural power of space and space travel were also reflected in Tyson’s speech as the Keynote presenter at

the 2013 National Space Symposium.

Commenting

of the consequences of space exploration insofar as their effect on America’s

intellectual health is concerned, he said:

So what

are the current problems here in America? Not in other parts of the world. Our

economy is in the toilet. Hardly anyone is interested in the STEM fields,

meanwhile our best minds are going overseas. Politicians are pretty sure they

have a solution to that, let’s get better science teachers, how about our jobs

going overseas, how’s about moving some tariffs and contracts? People are not

innovating so we put money in innovative initiatives. There things are all band

aids people. They don't work.

Proposing

a doubling of NASA’s budget, he continued, saying:

Whatever

the motives, be they geopolitical, military, economic, space becomes the

frontier, and you know every week that some new innovation is going to be

proposed, new patents are going to accepted. Space is exciting. These

innovations make headlines, and these articles filter down the educational

pipeline, everybody in school knows about it. You don't have to set up programs

to convince people that being an engineer is cool, they will know it just by

the cultural presence of those activities.

You do

that it will jump start our dreams. And you know that innovation drives

economies, especially true since the industrial revolution.

Convinced

that we’ve stopped dreaming about tomorrow, Tyson argues that NASA is needed

for more than just scientific progress. A national effort to become more

involved in the exploration of the cosmos will, he claims, reinvigorate our

collective culture as well as the economy.

Despite

provoking controversy from certain religious groups, Tyson has also frequently

appeared on popular shows like The Colbert Report to promote the funding

of science and interest in scientific endeavors among the public at large. He

has been a leader in using social media to engage with his fans, with more than

3 million followers on

Twitter.

Bill

Nye is another vocal advocate for science in mainstream culture. A former

mechanical engineer at Boeing, Nye hosted a television show called, Bill Nye the Science Guy, throughout the '90s. He used

humor and easy-to-replicate experiments to demonstrate to children how

scientific concepts relate to everyday life. Since the conclusion of his show,

Nye has frequently appeared in other shows and series with a scientific bent,

including 100 Greatest Discoveries and The Eyes of Nye. In recent

years, Nye has used his stature and popularity to advocate for the reality of

global climate change, encouraging sustainable energy and the importance of

scientific literacy.

While

it seems impossible to construe better science education as a bad thing, the

aforementioned champions of scientific rationality nevertheless face serious

challenges. Because many of the issues that they care about most are

politically charged, they often encounter opposition from people on the other

side of the facts. This has led some of their adversaries not only to question

the validity of certain views held on specific topics, but overall value of

science and its capacity to illuminate the natural order of the universe.

Additionally, in certain subsets of the population, science is perceived to be

a dull business, only of interest only to “nerds” and other socially

maladjusted individuals.

It's

clear that understanding facts about the world around us will likely become

even more important as scientific discoveries play an ever-increasing role in

daily affairs. The strength of the United States as a society will hinge on the

ability of the electorate and government officials to enact policies that

promote a better understanding of science and the natural world. Science

communicators therefore have an important role to play in educating the public

on matters that affect every one of us.

Space as Culture by Neil DeGrasse Tyson (Keynote speech at the 28th National Space Symposium)

Space as Culture by Neil DeGrasse Tyson (Keynote speech at the 28th National Space Symposium)

Carl Sagan Writes a Letter to 17-Year-Old Neil deGrasse Tyson (1975)

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário