For nearly a decade now, we have been warned about an upcoming generation spawned from the electronic motherboard of interactive entertainment -- a youthful tribe of digitally-oriented citizens known as the Nintendo Generation. This is a stimulus-craving generation for which the video game replaces family interaction, supplants physical activity, and renders intolerable the unstimulating chore of reading held dear by the print-oriented literati for nearly five centuries. The Nintendo Generation is composed of misplaced, hyperactive digirati, highly specialized in the most advanced forms of entertainment and telecommunication, born on the cusp of rampant familial disintegration and overwhelming global unification. In an ongoing search for ecstasy, the young, fin-de-millennium digirati isolates himself from immediate social contacts, and channels his mental and physical energies into an ongoing war--a war waged against faceless opponents who are plugged into their individual outlets all along the fibre optic battlefield.

Yet the label of Nintendo Child is not limited to the video game enthusiast. Any child raised in the cable TV, music video, channel-flicking environment must be classified as part of the Nintendo Generation. In order to change channels, the pre-digital child had to get up from the sofa and turn the analog dial to any one of a sparse selection of local networks. The digital child, on the other hand, remains almost completely motionless before the screen, negotiating a dizzying landscape of visual images with the flick of a thumb or forefinger. In short, the remote-control-wielding channel-surfer is very much akin to the joystick-handling video game jockey--both seek solace before an interactive screen, enraptured by the flow of images which they (at least in part) control, while all the time vacillating endlessly between boredom and ecstasy.

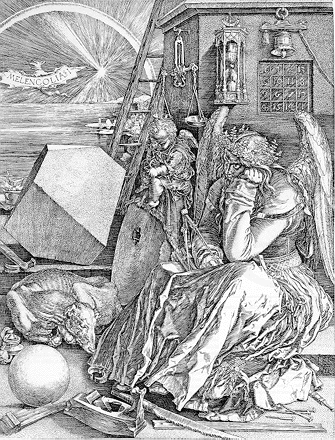

Notably, the Nintendo Child, rendered powerful before the video screen, has little chance of finding entertainment in the non-video world -- a world which is comparatively slow-moving, drab, and which may not be altered by the flicking of hand-held digital prostheses. Whereas the realm of video is explosive, brilliant, hyperstimulating, the real world lacks lustre--it is disillusioning, boring, unstimulating. We might even say that the prevailing mood of the Nintendo Child--aside from brief ejaculations of digital ecstasy--is melancholy. A melancholy comparable to the dark sobriety of the reformed drug-addict or alcoholic who forever abandons a heightened plane of experience. A melancholy that is reflected in the most prominant arts of the era: in fashion for which black is the only rule; and particularly in music, where such self-piteous and mundane lyrics as "I'm a creep," and "I'm a loser," are the anthems of an entire generation.

Ironically, just as the Nintendo generation seems to be reaching its cultural apex, Nintendo Inc. has ceased to be the grand facilitator of digital melancholia. The new God of video gaming is Sega, and the most powerful opiate for the digital masses is now the Sega Saturn system. In effect, the word Saturn encapsulates the very dichotomy that video game entertainment represents for the young digirati. In Ancient Greece, Saturn was identified with unrestrained merrymaking, orgy, ecstasy. Yet during the Renaissance, the word Saturnine began to be associated with sloth, melancholy and boredom -- Saturn was used as the alchemical term for lead. It is appropriate then, that Sega Saturn is a device which encourages and facilitates the Nintendo Child's endless vacillation between boredom and ecstasy, between sloth and hyperactivity, between melancholy and merry-making.

Saturn permits the digital youth to escape the boredom and melancholy of real life through a powerful dosage of hypers(t)imulated reality--a surreality then, which like a drug-induced psychosis, can only be described in terms of extraplanetary exploration. "Head for Saturn," the advertisers suggest. "Sega Saturn is like nothing else on earth." And yet, this promise of ecstasy is juxtaposed with a visual non-sequitur: the bust of a young, melancholic girl with a shaven head, wearing the rings of Saturn like a cyber-punk crown of thorns. Evidently, this youngster has a head for Saturn.

It is a head prone to fits of melancholy, unless it is immersed in the extra-terrestrial unreality (extra-terrestreality) of electronic games.

It would seem then, that the ultimate escape from this melancholic planet would not be to head for Saturn, or to possess a "head for Saturn," but to be gifted with an actual "head of Saturn"--a cybernetic head, half human, half electronic entertainment system. As the advertisements suggest,

to really understand what life is like on Saturn, look inside your head. There, in the inner realm of rods and cones, of optic nerves and ear drums, is where the Sega Saturn experience breathes. Three 32-bit orchestrated processors, 16.7 million colors, lightning-quick texture mapping, connoisseur-class surround sound, and amazing first-person perspectives immerse you in worlds of entertainment you've never experienced.

This is not just a "head for Saturn," but a "head of Saturn".

A utopic, cybernetic head conceived by the Sega God at the time of Genesis (Sega's original video entertainment system). By proclaiming to its consumers that "IT'S OUT THERE," the Sega God is not prophesying about a Promised Land on another planet. S/He is prophesying about a virtual extra-terrestreal oasis that only a cyber head would allow. S/He is promising a perpetual ecstasy which may be achieved without physically abandoning the Earth. Yet the Sega God's promise of ecstasy-through-video-narcotics is undermined by the war-camp aura of Sega's melancholy mascot.

There is nothing ecstatic about the Saturn Lady. Sega Saturn and other video game systems can only cause an escalation in the phenomenon of digital melancholy -- unless, of course, the Nintendo child is allowed to spend virtually all of his time immersed in the simulated world of video games--a solution which has been made accessible through such hand-held prosthetics as Game Boy and Game Gear. Unfortunately, these digital syringes of the Nintendo Child are beyond the scope of this study, and shall have to be examined at a later time.

*First Appeared in Dodo Magazine, July, 1995.

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário